What’s in this newsletter:

- Embracing mortality led to choosing a different path.

- Nerd fact of the week: What are OS and FPS?

- What’s next: Caring for Caregivers with Dr. Nirav Shah, Senior Scholar at Stanford University's Clinical Excellence Research Center

Embracing my mortality led to choosing a different path.

People are often surprised when I say that going through cancer was one of the best things that ever happened to me. I don’t mean to say it wasn’t hard, or that it was not without challenges, but it did allow me to make different choices about my life. I’ve always been someone who has believed that you create your own destiny. I was raised to work hard and create my own independence. I’d choose work over just about everything else. I usually joined a high growth startup where I could have an impact and “grow” in my career. “Growth” meant professional development and conventionally defined success. That did come at a cost. The cost was my health. It crept up on me. I am not suggesting that ignoring my health caused cancer, rather that my health did not capture my attention until it was whittled away.

When the cancer diagnosis happened, life came to a crashing halt. Everything I had worked towards and built my life around vanished overnight. All those “successes” amounted to very little. For those of you science and math folks out there, it was as if the signal-to-noise ratio changed overnight. The key question was: What was life signaling to me?

I spent the majority of my treatment, which lasted over 19 months, ignoring that question. It lurked somewhere in the background of my consciousness. Then the treatment ended. I had successfully built a dam that had walled off the emotions. After my last infusion, that dam broke. The flood of emotions threw me into a fast moving river where I struggled to hold onto a flimsy branch.

That was when 2 conversations happened. I can no longer remember which came first, but they somehow built on each other.

The first happened with a now deceased individual whom I consider a mentor and friend, even though I never met him. Professor Morrie Schwartz, a Professor of Sociology at Brandeis University died in 1995 from ALS. Mitch Albom, his student, interviewed Professor Moore in the last phase of his life, and summarized the lessons in a book named Tuesdays with Morrie. One quote that has stayed with me was Professor Moorie telling Mitch —

“Our culture doesn’t encourage you to think about such things until you’re about to die. We’re so wrapped up with egotistical things, career, family, having enough money, meeting the mortgage, getting a new car, fixing the radiator when it breaks—we're involved in trillions of little acts just to keep going. So we don’t get into the habit of standing back and looking at our lives and saying, Is this all? Is this all I want? Is something missing?...If you accept that you can die at any time—then you might not be as ambitious as you are.”

The second conversation was also with a mentor and friend. This one was in person at a local cafe. He had seen me go through some gnarly moments through cancer treatment. We were supposed to be celebrating the end of infusions. However, the end was daunting. I felt more vulnerable than I’d ever felt as a patient. I was angry and sad. There are things about cancer that are difficult. Then there are things about the cancer experience that do not need to be this hard. I was angry about those things - the things that shouldn’t be hard. He encouraged me to write about what I might want changed in oncology. He asked me that classic, annoying, magic wand question. If I had a magic wand, what would I change? I spent the next 3 months writing an answer to that question.

Those months of writing forced me to reflect on my time. No matter what type of cancer you have, be it a curable cancer, an incurable slow growing one, or a fast growing cancer, you end up thinking about time. Sometimes the answer is weeks, months, years, or decades. Most often, the answer is probabilistic, and goes something like this: “Given the data we have (or don’t have), you probably have (or don’t have) <insert duration>.” The point being, we have no idea how much time we really have left.

For me, the magic wand question was intricately tied to time. How much did I really have? In my case, treatment had achieved its curative intent. However, the data essentially only tells you there is a high probability that I will, in fact, live to 5 years. Thus, I had to develop my own framework for thinking about it.

I asked and answered the following questions.

If I get 1 year, what will I do with my time?

If I get 2 years, what will I do with my time?

If I get 5 years, what will I do with my time?

If I get 10 years, what will I do with my time?

The answers surprised me. I realized that they didn’t change based on how much time I got. The answers were also really simple.

I’d walk in nature, play with my dogs, spend time with my family, and my community. I’d work out, eat healthy, and paint. I’d scuba dive. I’d work in oncology. I’d drive paradigm shifts. I’d start with the things about the cancer experience that should not be hard.

Nerd fact of the week:

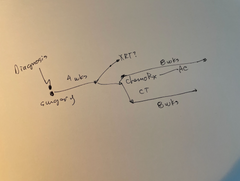

A lot of cancer research gauges treatment effects on “length of time.” They tend to use OS and PFS.

OS - Overall survival: The length of time from either the date of diagnosis or the start of treatment for a disease, such as cancer, that patients diagnosed with the disease are still alive.

PFS - Progression free survival: The length of time during and after the treatment of a disease, such as cancer, that a patient lives with the disease but it does not get worse. (Source: National Cancer Institute).

For a cancer drug to be effective, it ideally moves the needle for at least one of the two survival markers.