I grew up in Kolkata, India. Kolkata (a.k.a. Calcutta) was the former capital of the British-Indian empire. It is one of the residual places in the world where art, culture, and politic supersedes capitalistic ambitions. The Kolkata milieu still meets in cafes to discuss philosophies, and Bengali artists propel the Indian art scene. The favorite pass time of “adda,” the seemingly topic-less discourse-based hangouts, is woven into the city's fabric. Against that backdrop, my encounters at Tata Medical Center in Kolkata should not have surprised me.

Although I grew up in Kolkata, I was diagnosed and treated for cancer in the US. Here inspiration and hope are thrown at you, the cancer patient, like candy. Phrases like “you got this,” “it’ll all be okay,” and “you are a warrior” flow throughout the day. On the more challenging days, they help. On others, they can feel contrite. Inspiration is everywhere - quotes on social media, cancer stories in movies, and stories in every little booklet you get your hands on. Patients' battles against the disease are seen with pride. In the US, they are celebrated publically across the news and media. After 2 years of active treatment and another year into survivorship, I feel exhausted from the inspirational commentary.

When I went home to India after a four-year hiatus, I was curious to see how the cancer community and the fabric of India's heterogeneous culture interacted. With a population of 1.3B people, mathematically speaking, cancer has and will continue to affect a lot of Indians. I knew that, unlike the US, cancer warrior stories were not everywhere. India hasn’t gone through the widespread cancer-ribbon movement that has taken over the US. Patient journeys against cancer don’t make local news headlines, nor does the latest book written by a cancer patient make it to local bookstores. In India, successful battles against cancer are celebrated privately within the confines of your immediate family. Inspiration isn’t readily available, and inspiring stories are whispered in the quiet corridors of the community.

Inspiration is a funny thing. While I am exhausted from the constant noise, an authentic moment of inspiration can offer a little nudge to get off the couch and go for a walk or temporarily relieve the pain from surgery. Then there are moments of inspiration that stay with you. They offer you a helping hand, guide your resilience, and offer will when there isn’t anything left. Unfortunately, these moments of inspiration are rare. For the last three years, I’ve had the fortune of experiencing it twice. One of them happened at Tata Medical Center.

Chemotherapy can be brutal. The class of chemotherapy drugs is extensive, with many treatments that do not result in the stereotypical cancer look. Then some drugs result in that balding, eyebrow-less, pale, weak, cancer look. I remember those days; looking at yourself in the mirror shocks you. What I remember clearly is the impact on my diet. I would lose and regain 20 lbs within 10 days. The instructions from my oncologist were - to eat whatever you could tolerate. If someone had restricted my diet in those days, the experience would have been more challenging. Often small candies were all I could handle. The experience of sucking on a hard candy would enable my mouth to feel like my mouth and not some metallic cave. Food usually tasted abysmal, and I began associating it with feeling very ill.

A family friend heard of our work at Manta Cares and invited me to join her at Tata Medical Center (TMC). She and a few others had formed a group to support the pediatric wards at TMC, which saw patients from West Bengal, neighboring states in India, and neighboring countries. TMC, a non-profit, had set up one of its most prominent centers in the country. Patients and caregivers hailed from various countries and cultures and spoke several languages. My family friend had established a ritual of visiting the pediatric wards, spending time with the kids, and offering hospital-approved toys, lollipops, crackers, and cookies. She wanted me, a survivor, to walk around the ward as someone who had survived the ordeals of cancer treatment. I was meant to inspire. So I walked with her on this day, trying to connect with the kids and families offering candy.

We were in a ward with six beds. I offered a lollipop to a five-year-old boy a few days after an intensive round of chemotherapy. He looked at the lollipop and shook his head, saying no. I looked at him quizzically, wondering why a child post-chemo was saying no to candy. Before I could gently offer it again, he looked at me and said, “sugar is bad for me.” I was stunned. He was right; sugar isn’t the healthiest option in the world for cancer treatment. Plus, these were hospital-approved snacks. I didn’t overthink it.

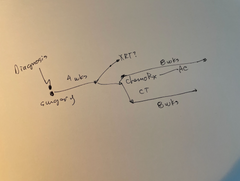

After spending a few minutes, I moved to the next bed. There was a 3-year-old. The same thing happened. Then it happened again with a 13-year-old, then with a 6-year-old, then with a 10-year-old. This happened again in the adjacent ward. My bag of little toys was getting lighter, while the lollipop bag remained largely untouched. So here I was, 3 years after my initial diagnosis, struggling to stay on track with my diet, losing motivation to stick to the lifestyle modifications I had promised my oncologist. Compared to these young kids, who, days after a bone marrow transplant, intensive surgery, or chemotherapy, had the fortitude to say no to something that every child craves shook me up. To have that strength to stick to your commitments during days when you have nothing in your reserve is inspirational.

I had been invited to share my story to inspire hope in survival, yet I don’t think I was the inspiring one. Those brief moments felt like a lifetime had passed when these kids could stick to their resolve in some of the most challenging moments one could imagine.

It reminded me of the words of Rudyard Kipling.

If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew

To serve your turn long after they are gone,

And so hold on when there is nothing in you

Except the Will which says to them: “Hold on”;

My interactions at TMC were fleeting, but I walked away with more hope than I’d had in a long time. I resolved to stick to my principles; I yearned to remain motivated without external drive; I felt inspired to look within for strength when exhausted; and I was inspired to rebuild the health I had lost.