Today there are over 1300 medicines and vaccines in development for cancer, all in clinical trials or being reviewed by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). As a biological engineer who works in the healthcare space, I have come to know the importance of “congresses” in specialty areas. These congresses aggregate the world's best experts, researchers, doctors, hospitals, and often pharmaceutical companies to ensure the clinical community is up-to-date on the latest research, treatment options, and diagnostic tests. In the world of oncology, there are several such “congresses.”

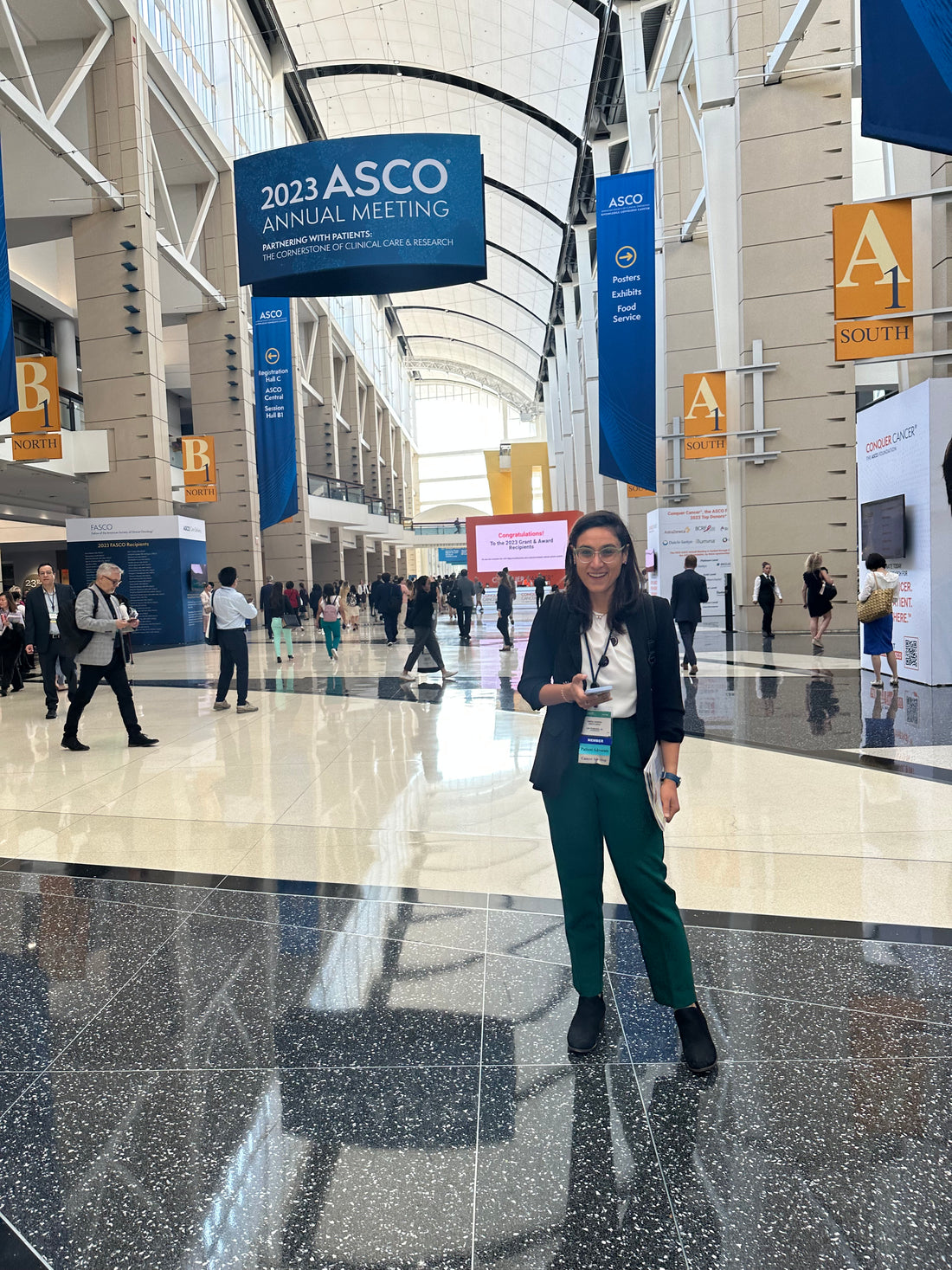

The largest and most prominent is the ASCO, the American Society for Clinical Oncology hosts. Every year in June, the global cancer community descends upon Chicago. In 2023, over 40,000 individuals came in person to ASCO. ASCO is a US-based organization primarily focused on advancing cancer care and supporting oncology professionals. ASCO provides a platform for oncology professionals to collaborate, share knowledge, and stay updated with the latest advancements in cancer research and treatment. The society organizes annual meetings, conferences, and educational programs to disseminate information on cancer-related topics, including clinical trials, treatment guidelines, and supportive care.

As a cancer patient, one would rarely hear of or interact with ASCO. However, unknown to most patients, ASCO has profound implications for our experiences. ASCO congregates the world's cancer community to showcase the latest research, determine the updates to treatment recommendations, as well as educate our doctors on what are the latest approaches to diagnosing and treating cancer.

As a patient advocate, the Manta Cares team showed up in full force to the 2023 ASCO conference. This year’s theme was “Partnering With Patients: The Cornerstone of Cancer Care and Research.” Dr. Eric P. Winer, the President of ASCO gave the keynote speech. There were a number of themes that stood out for us. Below, we have summarizes the theme and insight, and included an excerpt from Dr. Winer’s keynote speech.

1. Patients need to be treated as partners to their doctors.

“My presidential theme, “Partnering With Patients: The Cornerstone of Clinical Care and Research” builds on my oncology career of more than 30 years and resonates with many of the challenges in oncology today. The theme promotes the preeminence of the relationship between the patient and the oncology clinician, which should be neither hierarchical nor unidirectional.

Some oncologists harbor concerns that they don’t have the time to establish a partnership with each of their patients, and I understand their apprehension. But I believe we must form these partnerships if we want to provide the very best cancer care and encourage our patients to participate in clinical trials.

2. Lived experiences as patients lead to true empathy, and hopefully, a desire to change the healthcare system for the better.

My own thoughts about partnerships are influenced by my clinical work and my experiences beginning in childhood as a patient. Make no mistake, I do not think that one needs to have a lived experience as a patient either to understand or pursue an effective partnership with those for whom you care. Like my mother’s father and two of his brothers, who died in childhood, I was born with a bleeding disorder, hemophilia, in the era before effective treatments were available. I spent much of my childhood at Boston Children’s Hospital in a revolving door of hospitalizations and prolonged clinic visits to address recurrent bleeding episodes. My mobility was often limited, and my elbows were forever either bleeding or recovering from a recent bleed.

3. As a patient, seeking doctors who hear you, listen to your concerns, and are willing to create partnerships is critical to trust and confidence in the care you receive.

As I look back, I realize how much my parents sought out doctors who would partner with them and quickly moved on to a new physician if their voices were not heard. After all, they were experts in what I was going through. My father formed a lasting partnership with a forward-thinking orthopedic surgeon who taught him how to fashion splints to fit any joint, and that relationship not only kept me out of the hospital countless times, it provided all of us with tremendous confidence.

4. Stigma exists even within the clinician community. As a patient, sadly, you can be denied treatment for no fault of your own.

In 1985, before I had even been tested for HIV—after all, there was no rush to be tested as I had no symptoms at that time and there was no treatment—I went to see my dentist for a much-needed root canal. As I was lying back in the dental chair, he entered and, with barely a greeting, asked me to leave the office. He claimed the staff had refused to treat me because of the risk they thought I posed. I was abruptly denied access to care that I needed. I felt helpless, angry, and rapidly understood the power of stigmatization. I cannot tell you how relieved I was when I found a wonderful young dentist who took me into her practice.… Illness is hard, but illness that leads to stigmatization is crushing. This was true of HIV for years, and my outrage would peak when people commented that I contracted HIV in a so-called socially acceptable manner.

5. “If you scratch below the surface, everyone has a challenge in their lives—small, big, or bigger.”

By the early 90s, I had the foreboding sense that I might not live a long time. I had developed symptoms, and could not ignore the drenching night sweats, the mouth sores, the persistent rashes—and the mounting deaths. I was as frightened by what I might have to go through and put my family through as I was of dying.

Nancy and I were living with uncertainty and residing in a bubble of secrecy. Would our children be invited to play at the neighbor’s house if our neighbors knew that their father had HIV, and for that matter hepatitis C as well? I also doubted that my patients would want to see me if they knew about my health. I was leading a double life and guilt became my daily companion. So, too, was the fear that I might not be able to keep my job and what that would mean for our family and me personally, given my role and identity as an oncologist.